In the year 1971 in Brazil was a place where people were hesitant before approaching general Emilio Garrastazu Medici. The PresidentPresident was a feared persona whose brutally brutal military regime relied on systematic torture and execution of those who opposed him. However, Lea Campos was about to visit him.

Campos believed that Medici could aid her struggle for power with Brazil’s sports authorities – under the omnipotent Joao Havelange, who would soon be the PresidentPresident of the world’s football governing institution Fifa.

Four years prior, Campos had qualified as a referee. She was among the first women to do this; however, the CBD, the body that was in charge of all sports in Brazil, did not allow her to do so.

This South American country was one of several countries where women’s organized football was prohibited, as was England was the other. In fact, the legislation passed in 1941 banned women from Brazil from several sports. Havelange, who was the head of the CBD in the CBD since 1958, believed that the ban was also applicable to refereeing. According to Campos, He made his opinions explicit.

“Havelange first told me that women’s bodies weren’t suitable for refereeing men’s games,” Campos now 77 tells BBC Sport.

“He later stated that having periods could make my life more difficult. He eventually argued that women were not referees so long as the man was in the helm. “

It wasn’t its first time Campos had to fight to get a break from the sport she adored.

The actress was born on the 25th of April 1945 in Abaete, a tiny town located in the southern part of Brazil in Minas Gerais. Campos became keen on football from an early age. She recalls fondly the kicking of improvised bundles constructed from socks. First, however, she had to contend with the wrath of everyone.

“I was always trying to play football with the boys at school, but teachers would stop me and say it wasn’t appropriate,” she says.

“As to the parents of my mother, they declared that it was not a good thing that a woman should be involved in. “

The father and mother both urged her into beauty contests instead. She was consistently a winner in competitions. Ironically one of her wins in 1966 helped her get employment in public relations for the top team in soccer, Cruzeiro.

Campos was a part of the team that travelled throughout the country. Her interest in the game rekindled. Then it occurred to her. Perhaps there was an opportunity for her to become engaged in this game, after all.

“If I tried to play, it would have been impossible to get support for the cause, as it was actually illegal for women to do it at that time,” she states.

“But being an official referee was one method of gaining access to the job. There was no specific prohibition to be against this in law. Besides, while women were not allowed to kick an object, however there was no reference to blowing whistles. “

The year was 1967. Campos was enrolled in an 8-month training course for referees and graduated in August. Although she may not be the first woman anywhere in history to do this – finding the first female football referee is more complex than it initially seems.

In 2018, it was reported that Fifa recognized the name of a Turkish female, Drahsan Arda, as the first in a letter addressed to her. Arda was granted her license as a referee in November 1967 and took control of her first match in June of 1968. She submitted supporting documents to Fifa and received a response, which Fifa’s claims were misinterpreted. Instead, it just acknowledged that she was among soccer’s very first female officials.

A different candidate has been discovered. A third candidate has recently been found – Ingrid Holmgren, a Swedish woman who has completed her training in 1966. Edith Klinger is also an Austrian who is believed to have served as a referee in 1935.

Fifa isn’t capable of stating with absolute certainty who was the first, but it recognizes the importance of investigating this and is eager to aid in the investigation.

The only thing that can be confirmed can be said with certainty is Campos was among the first. But her admission to her program was only the beginning of a lengthy battle against oppressive patriarchy within the CBD. When she completed her studies, they refused to issue her a license, saying that the same law that bans female football players in Brazil also prohibited female officials.

“I sought legal advice and was assured that there was nothing in the text that made that distinction,” Campos declares. “But the authorities did not want to listen. “

After that, she spent years fighting for her cause with Havelange and the CBD along with Havelange. She sought to spread awareness by organizing friendly matches that she could officiate, including women’s games frequently removed by the police. In severe oppression in Brazil, the ‘dissent’ of this sort was not considered a joke; Campos asserts that she was arrested “at least 15 times” over a. “

In 1971, she received a note that provided her with the motivation to pursue her cause and was an invitation to take part in the non-official FIFA Women’s World Cup held in Mexico. She didn’t want to let this chance slip by; however she needed to get over Havelange and then become the unmovable hurdle.

The only solution was to turn to the power of a higher power. Campos’ beauty pageant history came to her rescue the second time around.

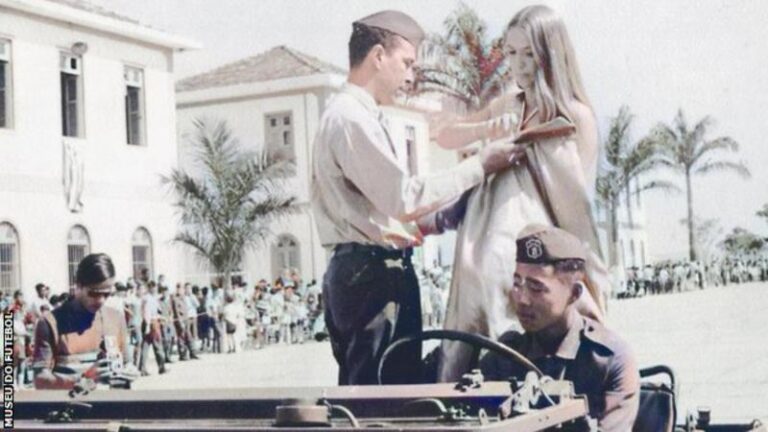

One of the numerous beauty competitions Campos had won was the title of ‘Army Queen of her home region of Minas Gerais region. She appealed to local commanders to assist her in securing an interview with president Medici, who was scheduled to visit the capital of the state, Belo Horizonte.

She was given three minutes. She explained to him that she was required to get over Havelange.

“Medici looked at me and said he’d like me to meet him at the presidential palace in Brasilia in a couple of days,” Campos declares.

“Needless to add, I was afraid. It was a government that was in a state of chaos and I was a rebel against the system. The thought of being detained or disappearing from my head. “

Campos promptly flew into Brasilia and was welcomed by Medici to eat lunch at the airport. In her amazement, the general was presented with a letter in which he asked Havelange to grant her a refereeing license. The general also revealed the most shocking discovery that she had admirers within the President’sPresident’s inner circle.

“One of Medici’s sons followed my career very closely and even had a scrapbook with pictures and newspaper articles about me,” she claims. “His collection was even bigger than mine! “

Maybe that’s why that led to Medici having to back down on Havelange. Whatever the reason, no one, not even the bigger-than-life Fifa president, would ever dare to question his directives. In July 1971, Havelange announced an event in the press and stated that after “a change of heart,” Campos will now serve as referee.

Campos states: “He even made a speech to the press stating that it was an honor to be able announce Brazil will have the world’s first female judge in the world, and it would be happening under his watching. “

After a couple of weeks, she travelled to Mexico but was struck down by the effects of the high altitude of Mexico City and was not competent to serve as a referee. Finally, when she returned home, she could work; however, having a license did not shield her from prejudgment.

The majority of the matches Campos was the referee for were lower division matches across Brazil where a woman referee was advertised as an exotic attraction.

Sexism and insecurity were prevalent in her work. Newspapers produced several cartoons that were not in good taste. One cartoon suggested that players might be enticed by female officials.

She remembers an under-23 game between state rivals Cruzeiro and Atletico Mineiro in 1972.

“Before the match, an Atletico director approached me and lifted his shirt,” Campos claims. “I was able to see that he was carrying an arsenal.

“Cruzeiro was 4-0 up and after the game, I noticed the same guy at the end of the tunnel. I asked him if he would like for me to be shot. Instead I was given hug and told me I had played well. “

In the end, Campos says, she wasn’t treated in any way differently than male referees.

“OK, sometimes players would get a bit angry,” she says. “There was one who refused to leave the pitch when I sent him off. There were other occasions when players would tell each other off for swearing in front of me. Most of the time I felt really respected. “

She was also content. Then came a devastating life-altering accident.

The year was 1974. Campos travelled on the bus when it crashed into the back of a truck. The accident left her with horrendous injuries to her leg, which almost required amputation. But, in a twist of irony to the incident, her bus travelling on was part of a business owned by the Havelange family.

Campos endured more than 100 surgeries and was in a wheelchair for two years. Most of her treatments were carried out in New York, where she was introduced to Luis Eduardo Medina, a Colombian sportswriter, who she was to marry in the 90s and move into America. The United States.

In America, she re-invented her life as a baker and was a massive hit with the Brazilian ex-pat community of The New York and New Jersey region. Later on, her health began to decline, and she experienced 2 heart attacks. The most challenging time for her was in May 2020, when the Covid-19 epidemic was a significant threat to her husband. Luis was fired, and the couple was faced with severe financial problems. At the time, they were forced to live in a relative’s home as they were homeless.

Then an online campaign by Brazilian referees generated enough funds to allow Campos and her spouse to afford an apartment located in New Jersey. So they’re weathering the storm, for now.

“What they did was beautiful, and I am really grateful,” Campos states. “It made me think that all my struggle wasn’t in vain and that I have left a legacy. “

She also screams with pride in the knowledge that women referees are taking over the game. They “punched the air” when French referee Stephanie Frappart became the first woman to referee a male Champions League match in 2020.

“I felt Stephanie’s success was a victory for me too,” Campos says.” It became clear to me that all I had to go through was worth it. I was the like a tree which is still bearing the fruit. “

The judge also believes that Frappart’s work was much overdue. Women’s referees have certainly improved a lot in the past few decades, but Campos is still adamant that some prejudices surround them.

“Why has there never been a woman officiating a men’s World Cup game?” she inquires.

“I really thought that things could be a little more advanced. Women and men referees both are both subject to identical training, so why should they be separated? It’s ridiculous. “